The robot does not exist. This might seem an absurd statement in an age where we’re surrounded by automation, conversing with chatbots, and marvelling at humanoid machines performing backflips. But pause. Step back from the immediacy of our mechanised world. Let’s ask: What is the robot, really? And does it exist in the way we imagine it to?

The Robot as Myth

Robots are not objects; they are ideas. They inhabit the space between fiction and reality, born from the fertile soil of human imagination. From Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. to Asimov’s laws, the concept of the robot has always been a projection of our fears, hopes, and questions about humanity itself. The robot is a mirror—one that reflects not only our technological aspirations but also our existential anxieties.

When you interact with a chatbot or watch a Boston Dynamics creation, you might be tempted to think, Here it is: the robot made flesh (or metal). But what are you really experiencing? A collection of sensors, circuits, and algorithms executing pre-programmed or learned behaviours. These processes, impressive as they are, do not make the robot “real” in the ontological sense. The robot exists only as a construct, a lens through which we interpret a collection of mechanical and digital phenomena.

The Ontology of the Non-Existent

For something to exist, it must have an essence beyond the sum of its parts. Does the robot possess such essence? A vacuum cleaner with a computer chip is not a robot until we assign it the identity of one. It’s the same with humanoid machines or AI systems. They perform tasks and mimic actions, but their “robot-ness” emerges only through human perception and storytelling.

Think about the term “robot” itself. It carries the weight of decades of cultural mythos, from dystopian androids to benevolent helpers. Without this narrative scaffolding, a robot is merely a machine—a tool. The very act of naming it a “robot” infuses it with a significance it does not inherently possess. Strip away the myth, and what remains? Gears and code. Inputs and outputs.

The Mind-Body Problem (For Machines)

Philosophers have long grappled with the mind-body problem: the relationship between the physical brain and the intangible mind. When it comes to robots, the question flips: is there a mind at all? A machine that “thinks” is not thinking in the way humans do. It processes. It calculates. It reacts. It does not dream, wonder, or doubt.

But here’s the twist: the robot’s lack of a mind underscores its non-existence. If the “self” of a robot is merely a projection of human meaning, then the robot is not a being—it is a metaphor. And metaphors, while powerful, do not exist in the same way as a tree, a river, or you and me.

The Robot as Simulation

In the postmodern tradition, Jean Baudrillard argued that in the age of hyperreality, the distinction between the real and the simulated blurs. The robot is a quintessential example of this phenomenon. It is a simulation of agency, intelligence, and autonomy. But it is not these things. It mimics them, creating an illusion of existence that we eagerly embrace.

When you tell a robot to do something and it responds, what you’re witnessing is not interaction but performance. It is a carefully choreographed simulation designed to evoke the illusion of dialogue, understanding, or presence. The robot, then, is not a being but a stage upon which our narratives of technology, progress, and control play out.

Why It Matters

To say that the robot does not exist is not to deny the very real impact of robotics and AI on our world. Machines shape industries, redefine work, and challenge our ethical frameworks. But by recognising the robot as a construct, we free ourselves from the trap of conflating simulation with substance. We stop asking, What can robots do? and start asking, What do we mean when we talk about robots?

This distinction matters because the way we frame the robot reflects the way we frame ourselves. Are we creators, wielding tools with intention? Or are we passive observers, dazzled by the illusions we’ve spun? By interrogating the ontology of the robot, we turn the lens back on humanity—on our desires, fears, and stories about what it means to exist.

In Closing

The robot does not exist. It is a spectre conjured by our collective imagination, a placeholder for questions we cannot yet answer. It lives in the space between the real and the symbolic, teasing us with its almost-thereness. To understand the robot is to understand that it is not a thing but an idea, not a being but a metaphor.

And in this revelation lies an invitation: to reconsider the stories we tell about technology and, in doing so, to reconsider the stories we tell about ourselves.

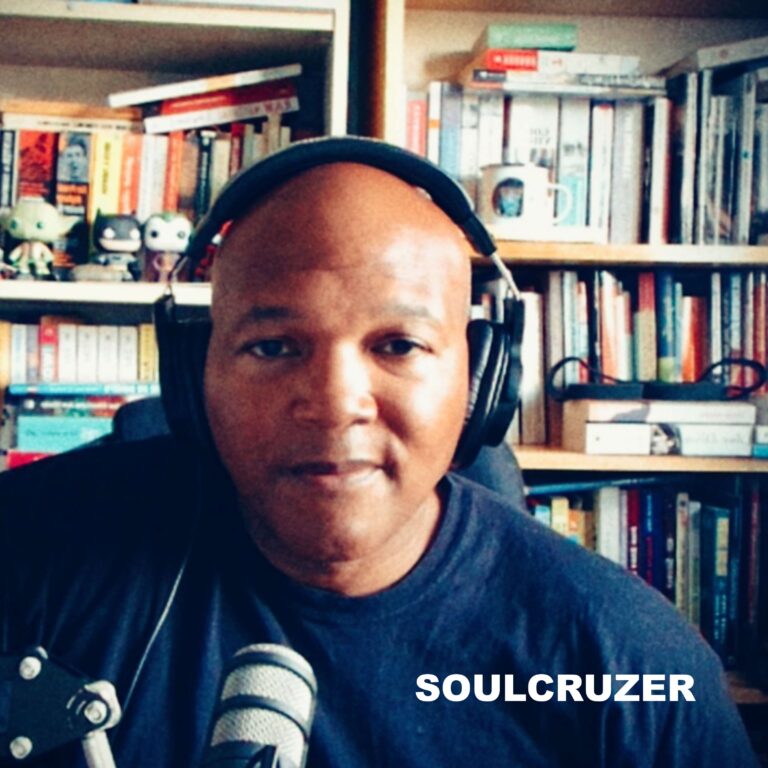

Discover more from soulcruzer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.